The road to treatment 17

On our 5th anniversary, Guy Lenaers gave us a presentation about the work he and his colleagues do at the University of Angers (France). The team of Dr. Guy Lenaers, consisting of 60 experts (30 medical professionals and 30 researchers), specializes in hereditary mitochondrial diseases and has unique expertise in characterizing mitochondrial physiology (the processes in the body). Mitochondria play a crucial role in generating energy (ATP) in cells. Guy Lenaers was one of the researchers who identified the relationship between the OPA2000 gene and ADOA in 1.

Research includes clinical diagnosis, trial analysis, understanding of mitochondrial physiology, therapeutic approaches and clinical trials. In Autosomal Dominant Optic Atrophy (ADOA), the patient's eyes are healthy, while the optic nerves are affected, which hinders the transmission of visual information from the retina to the brain. The optic nerves work day and night; visual information constitutes 80% of the information sent to the brain and therefore requires enormous amounts of energy and effective mitochondria. Therefore, in most mitochondrial diseases, the optic nerves can become dysfunctional. The effects vary from patient to patient, even if the same mutation affects individuals in the same family.

Despite the fact that the OPA1 gene was identified more than 20 years ago, developing gene therapy is very challenging. The main reasons for this are:

1. There are more than 400 mutations in the OPA1 gene

2. There are two distinct disease-causing mechanisms associated with OPA1 variants, haploinsufficiency and dominant negative effects

3. OPA1 genes code for 8 different proteins with different functions in the mitochondria

4. Too much OPA1 expression is also toxic.

First, the 400 mutations make it difficult to simply edit the gene, as this would require almost all families to receive separate treatments. Secondly, although it is possible to deal with haploinsufficiency by supplementing OPA1, sometimes the disease is dominant negative, meaning that the mutated gene has a negative effect on the normal gene. Third, some treatment approaches focus on restoring one OPA1 function while leaving the other functions unaddressed. Fourth, simply injecting a lot of OPA1 is toxic and can cause at least as much damage as no OPA1.

The possible solution to this problem in Angers is to use an approach called trans-splicing. When the OPA1 gene is damaged, it also produces damaged pre-RNA (an intermediate step between DNA and RNA), leading to pathogenic OPA1 proteins. Trans-splicing cuts off the damaged part of the pre-RNA and replaces it with a part that functions normally. This approach can be used for the vast majority of the 400 mutations; currently, approximately 80% of mutations can be corrected, corresponding to 90% of patients potentially treatable with this approach. Moreover, it also solves the other three problems related to OPA1 treatments. Currently, this approach is in the basic research stage, with some work still to be done in the laboratory, and the safety of the approach needs to be tested on monkeys. The development of this actual treatment requires a partnership with a pharmaceutical company that invests a significant amount (many millions of euros) to conduct clinical studies. If such treatments are developed, it does not mean that all patients will actually benefit from them, as these forms of therapies have a significant cost and health systems may be unwilling to pay for these therapies even after development.

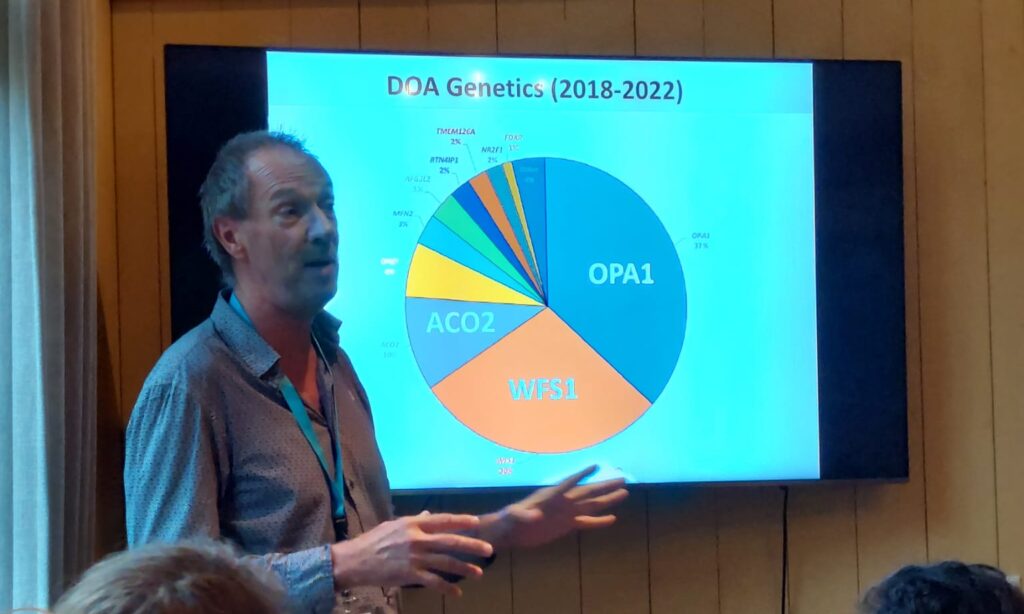

As of 2017, Guy Lenaers and his team found that only about a third of new ADOA patients have an OPA1 mutation, while a large number of other genes have been identified as related to optic atrophy, with the WFS1 and ACO2 genes being the second and third most important are. Currently, almost all planned RNA and DNA therapies target the OPA1 gene exclusively. This means that research into the treatment of other mutations must be started.

Another approach involves neuroprotectors, such as vitamin B3 (also called nicotinamide), spermidine and taurine. Neuroprotectors are a more general method of preserving visual function and do not rely on mutations. Guy Lenaers' team is currently involved in a study into the safety of B3, the results of which should be available in 2025. To further demonstrate the effectiveness of this approach, a double-blind clinical trial with at least 150 patients should be designed. However, B3 is an over-the-counter drug, there is currently no pharmaceutical company funding it for clinical trials. Such a trial would cost more than 1,0 million euros and is entirely dependent on public funding. At the same time, if the therapy works, due to the low cost of vitamin B3, health systems may be more willing to pay for this treatment.