The road to treatment 19

ADOA and ADOA+

On our Jubilee Day on November 18 in Doorn, René de Coo of the Nemo Mitochondrial Medicine group, Toxicogenomics department of Maastricht University, explained the operation of ADOA+ and the path to treatment.

ADOA is a mitochondrial disease in which the energy factories in the cell, the mitochondria, are damaged. Mitochondria produce the ATP molecule, which is needed to provide cells with energy (Figure 1). The cells in the optic nerve, the Retinal Ganglion Cells (RGCs), require a lot of energy, which is why the energy defect leads to damage there. Damaged optic nerve cells also lead to optic nerve pallor, a symptom of atrophy.

In 20-30% of cases there is ADOA+, which causes more damage than just the optic nerve. Main symptoms are hearing loss, CPEO, muscle pain, peripheral nerve problems, reduced steering, leg spasticity and rigidity.

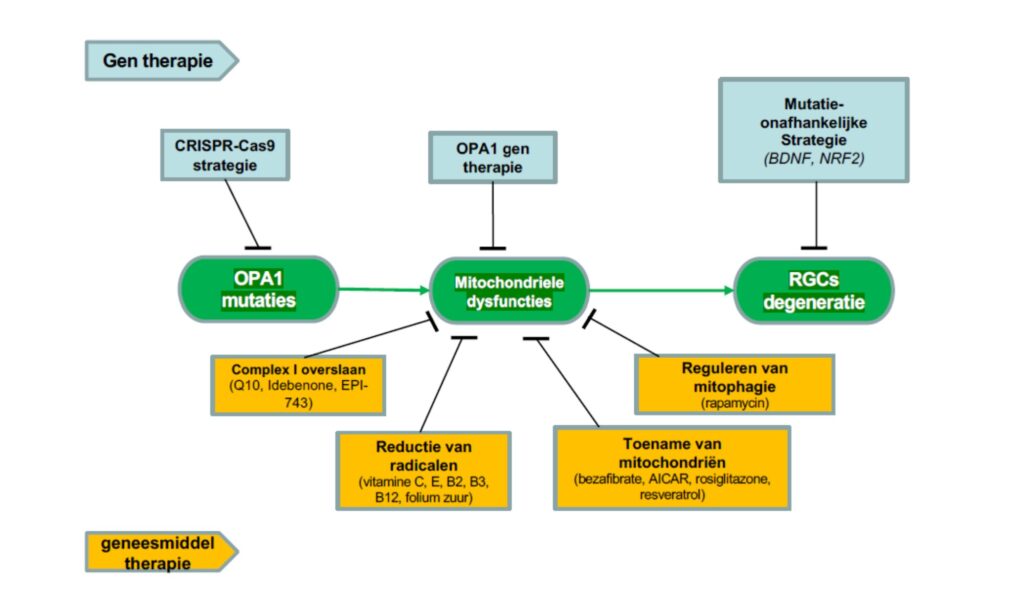

With the OPA mutation, the OPA1 molecule is produced incorrectly, as a result of which OPA1 cannot fulfill its normal functions. This causes damage to the mitochondria. In a healthy cell, mitochondria are constantly splitting and fusing, with even damaged mitochondria turning themselves off and being eaten by clean-up organelles (left side of Figure 2).

The right side of Figure 2 shows what this looks like in a cell with a damaged OPA1 gene. OPA1 molecule plays an important role in the fusion of mitochondria, and if it is not produced properly, the mitochondria cannot fuse, only split. Ultimately, the small damaged mitochondria are cleared away (mitophagy).

In 70% of cases this leads to optic atrophy. With ADOA+ there may be more than just damaged vision. For example, someone may be diagnosed with a drooping eyelid. This may already be ADOA+, depending on family history and the result of additional research. The results of these studies vary widely, but ADOA+ always involves additional (nerve) damage somewhere in the body.

ADOA+ involves a slightly different mutation than regular ADOA. The gene has the coding for the proteins, and these are represented by letters, like in a sentence. In a healthy person, the sentence is completely readable, and the protein can be produced. With ADOA, a letter is usually missing or added (nonsense mutation), causing the letters in the sentence to be incorrectly placed and the sentence to be unintelligible. This causes the protein to no longer function. With ADOA+ there is often a change in a letter (missense mutation) where the gene can be read but the meaning changes. This sometimes creates a real protein, which is harmful to the body. ADOA is more often associated with the production of less protein, with ADOA+ a disruptive protein is produced.

With ADOA+ the severity of the symptoms varies greatly, 12% have no symptoms. Inheritance through the female slightly increases the risk of ADOA+, and there is an increased risk of ADOA+ with a mutation in exon 14 of the OPA1 gene.

Various drug and gene therapies are currently being developed for ADOA (Figure 3). The drug therapies attempt to restore mitochondrial function. Some therapies target the ATP production processes (such as Q10, Idebenone, EPI-743), thereby restoring the function of the mitochondria. Others try to reduce radicals (vitamin C, E, B2, B3, B12, folic acid), others try to increase the number of mitochondria (bezafibrate, AICAR, roziglitazone, resveratrol), and others inhibit mitochondrial death (rapamycin) .

There are a number of gene therapies that intervene directly on the mutation (CRISPr-Cas), others try to solve the problems in the mitochondria (OPA1 gene therapy), and there are mutation-independent strategies that aim to stop RGC degeneration (BDNS,NRF2). .

What all therapies have in common is that they cannot yet be prescribed by a doctor.

Apart from treating current patients, it is also important whether it is possible to prevent ADOA from being passed on to future generations. There are options for this, and a clinical geneticist can advise on this.

With ADOA+, muscle weakness is one of the problems. An experiment was conducted at Maastricht University to administer one's own muscle stem cells to repair muscle weakness. This seemed to be safe in principle.

In summary, there is no therapy yet, but a lot of research is being done into the treatment of ADOA(+). Maastricht University is engaged in research into stem cells that can replace damaged cells. In the meantime, it is important for ADOA and ADOA+ patients to keep moving, which also protects the energy factories. Registration of ADOA gene mutations and donating skin cells can already contribute to research, and further support for research remains important.